WHAT IS A BOOK?

A book in its most general sense is a document or text recording something. It may not actually exist – it might be known of but lost, or it might lie in the eye of its potential author. To be useful, however, it needs to exist in a tangible form capable of being read. That now includes electronic forms, but Bookbinders are concerned in the main with the protective covering of a book recorded in some way on parchment or paper.

HISTORY

Ancient books and their materials

The oldest form of writing is the cuneiform (wedge-shape) found on clay tablets from the Middle Eastern region between the Tigris and Euphrates known as Mesopotamia (from the Greek for ‘between the rivers’), the modern Iraq and Syria. In about 3200BC the temple accountants of Sumer began to record their assets – animals, grain, financial records – with symbols based on pictures; these became more abstract, and were eventually used to record inventories, royal proclamations and literature.

Figure 1 Clay tablet (Louvre, Paris)

Figure 2 Cuneiform carved on a stone tablet from Erebuni

The Sumerian tablet shown is from Uruk; it is one of the earliest known and records the allocation of beer rations to workers. The later version in stone is from the ruined city of Erebuni in Armenia, and this form of writing spread over all the countries of the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean.

Other writing materials were used, such as wooden tablets filled with wax, but they decay easily and would have been destroyed by the fires that inevitably broke out from time to time. Clay tablets have the unique advantage of being made harder by fire, hence the extraordinary number of them that have survived, making the task of deciphering the script possible. They give a remarkably clear picture of life in the Ancient World. Cuneiform was used until the first century AD.

Wax tabletswere used extensively until Roman times; a reproduction is shown here.

Figure 3 A wax tablet

Papyrus had a variety of uses in Ancient Egypt – shoes, clothes, utensils, boats – and is made from beaten layers of the papyrus plant, which grew extensively in the Upper Nile area.

Figure 4 Papyrus plant

Papyrus was used all over the Middle East, and many papyrus fragments and scrolls still survive. This example shows a Greek script.

Figure 5 A sheet of papyrus with Greek script.

Parchment was invented in Asia Minor in very early times, and was the standard writing and printing medium until the use of paper became widespread in Western Europe in the fifteenth century. It is still used today by calligraphers as it has a very smooth surface. Technically it is the scraped and stretched skin of a sheep, while vellum comes from calves, but the terms are now often used interchangeably.

Figure 6 A sheet of parchment with a Latin text dated 1329.

(Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / The National Library of Wales

from Wales/Cymru [CC0])

The Codex

Parchment was often rolled into scrolls, like papyrus, but soon it was found more convenient to fold the skins and join them down the crease with leather thongs and sewing thread, thus forming the codex. Papyrus was also used for codices, but it tends to crack when folded so it lends itself better to rolling than folding. The libraries of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome contained scrolls and codices in both materials.

The codex became the dominant form, and has given us the shape of our modern books. The introduction of paper from China coincided with the development of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century and the mass production of books.

A short history of books right up to the modern digital form may be found on Wikipedia: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_books).

A selective bibliography may be found at the end of this article.

Bookbinding

The folded and stitched pages needed to be protected, and it was soon found that the best way to do this was to enclose them within stiff boards of some kind, usually covered with leather. In mediaeval times the boards were made from wood, and they are now made from paper pulp, but the shape is the same. You would have no difficulty in recognising the Codex Gigas as a book.

Figure 7 Codex Gigas, early 13thcentury.

Bookbinders are concerned with the way that the stiff boards enclose the stitched folds and make a protective cover; this is the binding. There are many ways in which books can be made but modern mass-produced books are either ‘paperbacks’ or ‘hardbacks’. Until about the 1960s most books were sewn (see below), including the Penguin paperbacks of the 1930s like the one shown here, but for cheaper books the back folds are now cut off and the pages glued together before the cover is added.

Figure 8 A Penguin paperback

Books stitched together along their folds are made up of an indefinite number of sections (also known as gatherings or signatures). These sections almost always have a multiple of eight pages, as they are laid out in order by the printer on a large sheet of paper which is then folded in a particular way. The first fold gives a ‘folio’, the second ‘quarto’ and the third ‘octavo’. When folded and stitched it is known as the ‘text block’.

Figure 9 Showing how pages are printed on a large sheet of paper and then folded to give book pages of octavo size.

Figure 10 A stack of sections ready for sewing to form a text block

Case-binding

The simplest form of bookbinding is the hardback book, known technically as a ‘case-binding’, as the cover is made up of boards and bookcloth and then glued on to the outside of the text block.

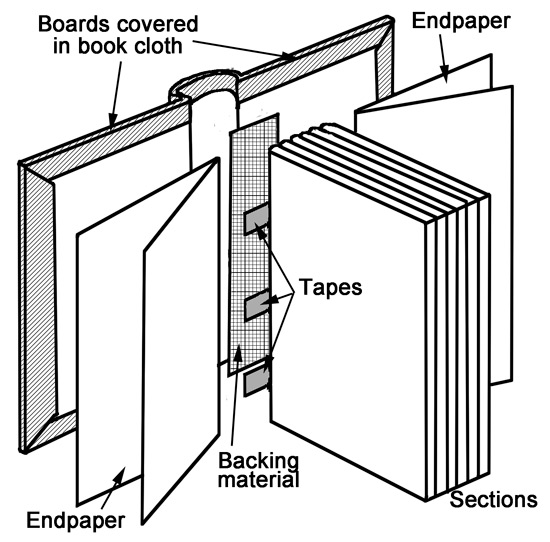

Figure 11 Diagram of the components of a case binding

The sections are sewn together on tapes, using a waxed linen thread.

Figure 12 Sections sewn to make a text block. Here cords have

been used rather than tapes as part of a hand craft

binding in traditional style.

Endpapers, a single fold of plain paper, are glued along the spine edge of the text block.

The text block is put in a press and is shaped and backed.

Figure13 The text block, sewn with tapes, is placed in a press

and the spine is shaped with a backing hammer to produce

‘shoulders’ on the block.

The cover is glued to the endpapers – see Fig 11.

Figure 14 When the text block is glued on to the boards, the unglued

book cloth on the spine forms a hollow, as in this case binding of 16 sections.

This hard cover is slightly bigger than the pages and so protects them better than a flush-cut paperback.

Figure 15 An inexpensive case binding with an embossed front board: the overlap of the boards, called by binders the square, is clearly seen. (Hiawatha, Longfellow, World Classic Series, OUP, 1925.

Leather binding

Leather is the covering material of choice for most craft bookbinders. It requires a stronger method of sewing, traditionally on cords rather than tapes, but both are now used. The endpapers are made up of several layers of paper and stitched in place, and the boards are attached before the leather is applied.

Figure 16 Boards are attached to the text block before the covering leather is applied.

The leather may cover the whole book, and is known as a full leather binding.

Figure 17 A book completely covered in leather is said to be fully leather bound

A leather book with a strip down the spine and corners is a half-leather binding.

Figure 18 A half leather bound book

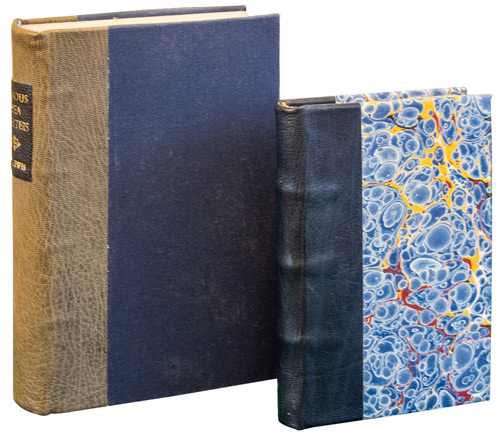

If it has just a leather spine it is a quarter-leather binding.

Figure 19 Two examples of quarter leather binding

The rest of the cover (the ‘siding’) may be bookcloth or paper, which is often marbled in attractive patterns, giving a pleasing effect.

Figure 20 A selection of marbled paper

Finishing

This term means the application of gold leaf to the leather cover and the creating of titles and other decoration by means of heated brass letters and patterns.

Figure 21 The electric stove for heating the handle letters and

other brass decorative stamps

Figure 22 Brass letters on wooden handles for placing titles on leather

Figure 23 Finishing tools used for tooling in gold on leather:

left to right – pallet, two pattern stamps, decorative wheel or roll

Figure 24 A fine example of elaborate gold tooling on a full leather binding

Rather than gold leaf that is used in tooling as in Fig 24, gold foil is now used for simple titles, such as oncase bindings.

Figure 25 This shows the gold foil being lifted after the title has

been applied to this cloth-bound case binding

Tools and equipment

Many of these are ordinary tools, such as steel rulers, hammers, knives of various sorts, large scissors and needles.

Figure 26 Some of the tools used by a hand binder. From left to right: glue brush, backing hammer, cobbler’s knife, pallet knife, steel rule, dividers, bone folder, scalpel.

The bonefolder is a tool that is peculiar to bookbinding. Other more specialist equipment includes presses to hold books both horizontally and vertically.

Figure 27 Finishing press with a rounded, backed and spine-lined text block

Figure 28 A nipping press

Figure 29 Tools for paring leather: top – a spoke shave, bottom – on the left

an English paring knife and on the right two French paring knives; in between,

other knives used for cutting and paring leather.

Other forms of the book

There are a number of variations on the traditional form of the book.

The Library-style binding was used extensively for public lending-librarybooks which needed to be as strong as possible to withstand handling by borrowers. They had a spine of leather or buckram (a strong book cloth), and reinforced endpapers and hinges.

Account book or springback binding was used for account books where the pages had to lie as flat as possible to allow for entries to be written over both pages and to be easily visible. It had a rigid hollow back joined to the cover boards in such a way that the book pages are forced to open out horizontally.

Figure 30 A dissected view of a springback binding which is used for

account books that have to open flat – note the spine in this type of

binding is a sturdy ‘spring’

Dos-à-dos bindings combine two books into one with the back cover of one being the front cover of the other. There are several historical examples of Bibles and Prayer Books being bound together so that the reader could just turn the book round to find the other part.

Figure 31 Dos-à-Dos binding – two books in one

Medieval Binding

There are many different styles of binding from this period which may be used today by craft binders. The ones shown in the figure all have the sewing exposed to view and the work has to be especially neat.

Figure 32 Four examples of medieval binding where the sewing is exposed

and the boards are of wood

New developments

Craft bookbinders will often look at new ways of binding books.

There has been a great deal of interest in recent years in Japanese binding where the paper is of very high quality and the stitching is outside the paper cover forming a distinctive pattern.

Figure 33 Some Japanese bindings

Cross-structure binding This dispenses with the paper cover and the paper-lined leather is cut so that straps cross the back of the book and the sewing is visible.

Figure 34 Cross structure binding – the structure of the binding is clearly visible

Design bindings

Leather is a wonderfully versatile material, and can be tooled, inlaid, pulled about or even airbrushed to achieve decorative effects. The best design bindings are real works of art. The figures show three examples and more may be seen by looking at the winning entries of the International Bookbinding Competition of previous years.

Figure 35 A fine binding in leather by Kathy Abbott which demonstrates various decorative techniques

Figure 36 A fine binding which is illustrative of the book contents by Paul Delrue

Figure 37 A fine binding by Lester Capon which takes a different approach to illustrate the book contents

Figure 38 Another fine binding illustrating a restrained approach. Tracey Rowledge, The Four Quartets

Book arts

Book artists push the boundaries further and use non-traditional techniques for artistic effect. Some of these can be quite spectacular.

Figure 39 A binding by book artist Tine Noreille

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS ABOUT BOOKBINDING

There are a huge number of books relating to the craft of bookbinding: its history, manuals of instruction, and subjects such as printing and paper-making. Here is a small selection.

Students wishing to pursue the subject further will find the following libraries useful:

The Frank Hippman Library (the Society of Bookbinders’ reference library),

The Birmingham and Midland Institute,9 Margaret St, Birmingham B3 3BS

Tel:0121 236 3591(ring first if you wish to visit). Website: http://www.bmi.org.uk/

See Hippman Memorial Library.

St Bride Foundation, 14 Bride Lane, (off Fleet Street), London EC4Y 8EQ

Tel: 020 7353 3331, Website: http://www.sbf.org.uk/

National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Rd, Knightsbridge, London

SW7 2RL. Tel. 020 7942 2000, Website: www.vam.ac.uk/info/national-art-library

Bookbinding practice

ABBOTT, Kathy. BOOKBINDING, A Step by Step Guide, Crowood 2010

BURDETT, Eric. THE CRAFT OF BOOKBINDING. A practical handbook, David & Charles, 1975.

COCKERELL, Douglas. BOOKBINDING, AND THE CARE OF BOOKS. A text-book for bookbinders and librarians. (The Artistic Crafts Series of Technical Handbooks), Hogg 1915, and numerous editions.

DOGGETT, Sue M. HANDMADE BOOKS, A&C Black 1998

IKEGAMI, Kojiro. JAPANESE BOOKBINDING, Weatherhill 1979

JOHNSON, Arthur. MANUAL OF BOOKBINDING, Thames & Hudson 1978

MIDDLETON, Bernard. THE RESTORATION OF LEATHER BINDINGS, LTP, American Library Association, 1972

MITCHELL, John. AN INTRODUCTION TO GOLD FINISHING, Standing Press, 1995. A guide to book gilding techniques

MITCHELL, John. A CRAFTSMAN’S GUIDE TO EDGE DECORATION, Standing Press,1993.

SMITH, Keith A. NON-ADHESIVE BINDING, Several vols. E.g. Vol. I. Books without Paste or Glue, Vol. II, 1-2&3 Section Sewings, Vol. III Exposed Spines; Keith Smith 1991 onwards

SUTTON, Angela. BOOKBINDING IN PICTURES, A beginner’s guide, Pantothen Books 2010

VAUGHAN, Alex. J. MODERN BOOKBINDING, Robert Hale 1929, reissued 1993.

Illustrative Books

Ed. FLETCHER, George. THE WORMSLEY LIBRARY, A Personal Selection by Paul Getty, Maggs Bros / Pierpoint Morgan Library. 1999

Ed. MILLER, Steve. 500 HANDMADE BOOKS, Lark Books 2008

History

CAVE, Roderick. THE HISTORY OF THE BOOK IN 100 BOOKS, Crows Nest 2014

DIEHL, Edith. BOOKBINDING, ITS BACKGROUND AND TECHNIQUE, Rinehart & Co. 1946, Dover 1980

McMURTRIE, Douglas. THE BOOK: THE STORY OF PRINTING & BOOKMAKING, OUP /, N.Y.C., 1943

MIDDLETON, Bernard C. A HISTORY OF ENGLISH CRAFT BOOKBINDING TECHNIQUE, New York & London: Hafner, 1963, Holland Press 1978.

NIXON, Howard M. FIVE CENTURIES OF ENGLISH BOOKBINDING, Scolar Press, 1978.

PEARSON, David. ENGLISH BOOKBINDING STYLES 1450-1800, British Library / Oak Knoll Press 2005

RAMSDEN, Charles. FRENCH BOOKBINDERS 1789-1848, Batsford 1950

SZIRMAI, J.A. THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEDIAEVAL BOOKBINDING, Ashgate 1999

TIDCOMBE, Marianne. WOMEN BOOKBINDERS 1880-1920, Oak Knoll Press / British Library, 1996

History of printing and related subjects

BARKER, Nicolas. THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AND THE SPREAD OF LEARNING 1478-1978. An illustrated history. OUP, 1978

CLAIR, Colin. A HISTORY OF PRINTING IN BRITAIN, Cassell, 1965.

HUNTER, Dard. PAPERMAKING, The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, Alfred Knopf 1943, Dover 1978

McKITTERICK, David. A HISTORY OF CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CUP , 1992-2004.

MORAN, James. PRINTING PRESSES, Faber & Faber 1973

MORISON, Stanley. FOUR CENTURIES OF FINE PRINTING, Ernest Benn, 1949, ‘student’s’ edition 1957

MOXON, Joseph. MECHANICK EXERCISES ON THE WHOLE ART OF PRINTING(first published 1677) Edited by Herbert Davis & Harry Carter, OUP, 1958, Dover 1978.